Carburettor icing is one of the most misunderstood hazards affecting light aircraft with piston engines. Many pilots associate “icing” with cold winter flying, yet official CAA guidance makes it clear that carburettor icing can occur across a surprisingly wide range of temperatures, including warm summer conditions.

How carburettor icing forms

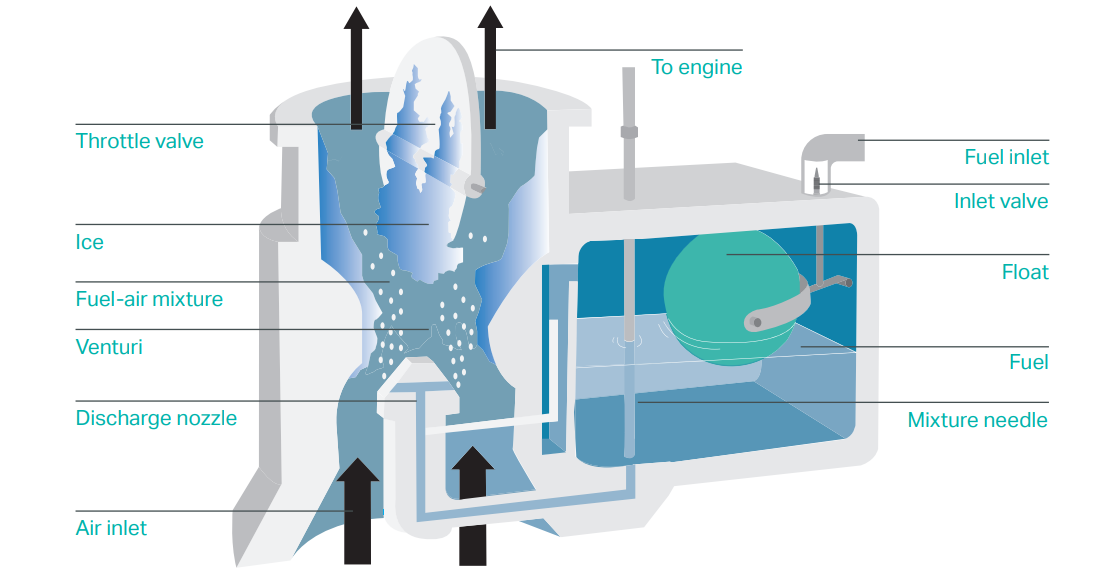

In carburetted engines, fuel is mixed with air inside the carburettor before entering the cylinders. As the air passes through the venturi, its pressure drops and the fuel is atomised. This process causes a significant temperature reduction inside the carburettor, sometimes by as much as 35°C below ambient. If moisture is present in the induction air, it can condense and freeze, even when the outside air temperature is well above zero.

As ice builds up around the venturi and throttle butterfly, airflow is progressively restricted. The mixture becomes richer and engine power reduces, often gradually enough to go unnoticed until performance is significantly degraded.

Conditions that increase the risk

The CAA highlights that carburettor icing is most common in humid conditions, particularly when operating at low power settings such as during descent. Temperatures between 0°C and 10°C present a high risk, but serious icing has been demonstrated at temperatures above 25°C with relatively modest humidity levels. In the UK and Northern Europe, where high humidity is common, pilots should assume carburettor icing is always a possibility rather than a rare event.

Recognising the symptoms

Early signs of carburettor icing include a gradual drop in RPM in aircraft with fixed-pitch propellers, or a reduction in manifold pressure in constant-speed installations. If fitted, an exhaust gas temperature gauge may show a decrease as the mixture enriches. Left uncorrected, carburettor icing can lead to rough running and, ultimately, complete power loss.

Prevention and correct use of carb heat

Most light aircraft prevent carburettor icing by using carburettor heat, which routes warm air from an exhaust heat exchanger into the induction system. Selecting carb heat typically causes a small power reduction due to the lower density of warm air, this is normal and should not be mistaken for a worsening problem.

When ice is suspected, carb heat should be applied fully and left on long enough for the ice to melt, usually at least 15 seconds. The CAA advises that rough running may temporarily increase as melting ice passes through the engine; however, carb heat should remain selected until normal operation is restored. Aircraft-specific procedures in the AFM always take precedence.

Final thought

Carburettor icing is not a seasonal threat, it is a year round operational risk. Understanding when it can occur, recognising the early signs, and using carb heat correctly are essential skills for safe piston-engine flying. Staying alert to the conditions, rather than relying on temperature alone, is key.

Reference:

UK Civil Aviation Authority, Safety Sense Leaflet 14 – Piston Engine Icing,